Was the militia intended to be used as an offensive military force in foreign lands? During the War of 1812, New England states not only said no, but they used the principles of the 10th Amendment to actively interpose and resist federal demands for mobilizing the militia.

BACKGROUND

Tensions between Great Britain and the United States had been growing for years. There were several factors involved, including:

- British impressment of American sailors – effectively kidnapping and forcing them to serve in the British navy.

- Interference with American trade and commerce. The British Navy attacked and seized over 400 U.S. merchant vessels between 1807 and 1812. It also blacked American access to some European and Caribbean ports.

- The British arming Native Americans who were resisting westward expansion.

As tensions increased in the spring of 1808, Congress, wielding the power “to provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia” in Article I, Section 8, Clause 16 of the Constitution, authorized the president to “at such time as he shall deem necessary, to require of the executives of the several states, to take effectual measures to organize, arm and equip, according to law, and hold in readiness to march at a moment’s warning, their respective proportions of one hundred thousand militia.”

By the time James Madison took office on March 4, 1809, diplomatic efforts to resolve the issues were breaking down, putting the U.S. on the path to another war with Great Britain.

As the 1808 law was set to expire in 1810, Madison went to Congress and asked for its extension. According to historian Gary Nobbs, “The concept became a debate over whether militia could be used in an offensive war across Canada’s border.”

This debate became quite contentious on the House floor. As Nobbs described things “it was decided that the militia constituted a military force but could not be used outside the United States unless they volunteered to cross a territorial boundary.” [Emphasis Added]

The House passed an extension, but the Senate delayed the measure and it never came up for a vote.

With war looming in February 1812, Madison signed the Volunteer Bill, authorizing him to accept up to 50,000 volunteers from the states.

The law left unresolved the same question debated two years earlier, as to whether the president could use these volunteers to fight on foreign soil, but an amendment that would have required volunteers to sign an agreement to serve outside the U.S. failed to pass Congress, indicating most members believed this wasn’t authorized, or good policy.

In April, Congress further authorized the president under Article I, Section 8, Clause 16 to order governors to “organize, arm, and equip” 100,000 militia troops. They were to be “held in readiness to march at a moment’s notice.” Each state was expected to fill a quota.

On June 1, 1812, President Madison delivered a special message to Congress enumerating U.S. grievances against Britain, and arguing that the continuation of the above-mentioned aggressive measures by the British amounted to a state of war against the United States.

“We behold, in fine, on the side of Great Britain, a state of war against the United States, and on the side of the United States a state of peace toward Great Britain.”

But despite war being waged against the United States, Madison refused to take any offensive actions without congressional authorization.

On June 18, 1812, Madison got it when Congress declared war on Great Britain.

Once war was declared by Congress, Madison was authorized by the Constitution to call forth the militia that had been previously armed according to the various acts of Congress.

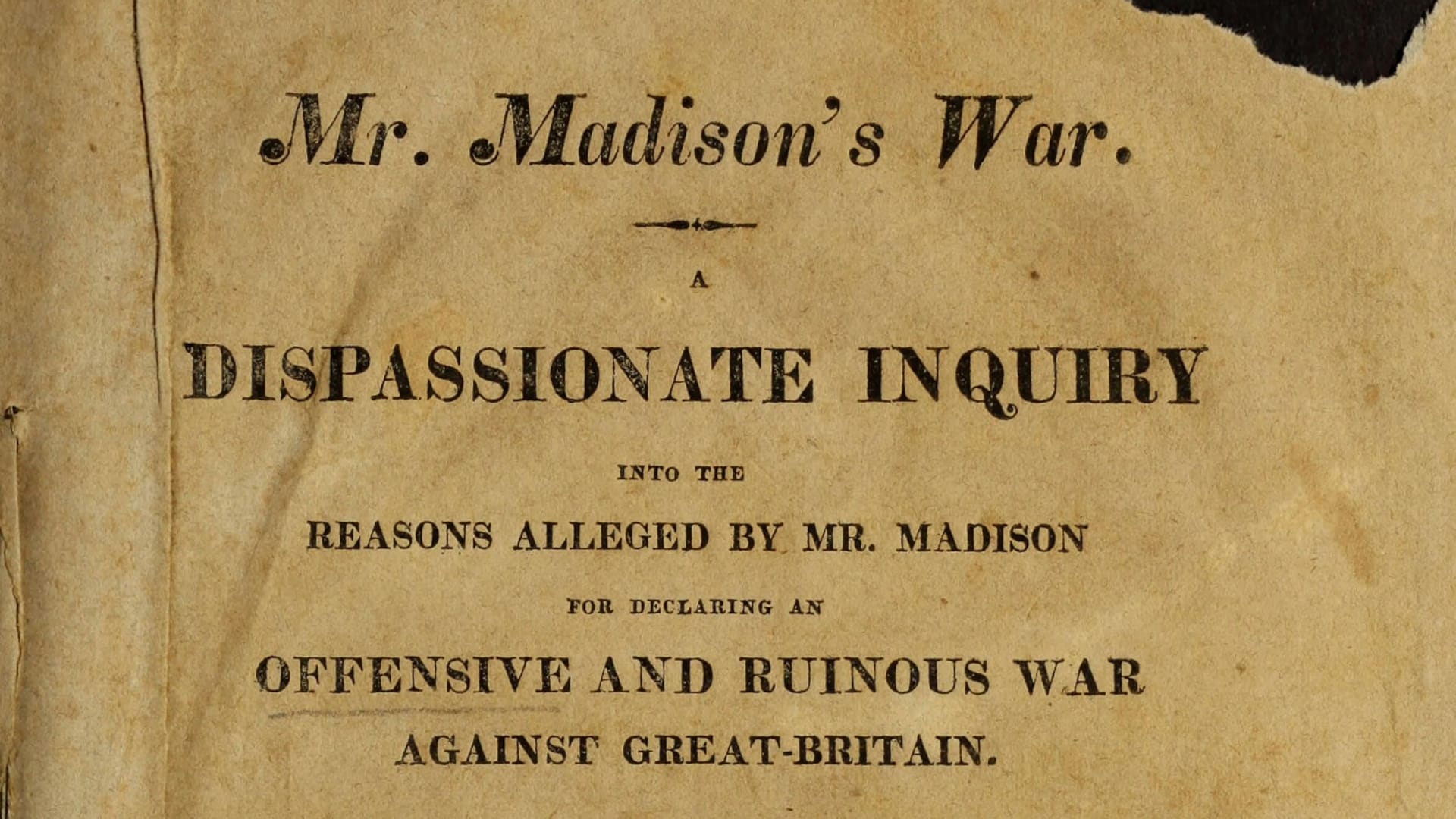

MR. MADISON’S WAR

While the declaration of war ended debate about Madison’s authority to wage war and use offensive military power against the British, it reignited the contentious argument about the federal government’s authority to use militias.

Article I, Section 8, Clause 15 of the Constitution authorizes Congress to call forth the militia for just three enumerated purposes.

- To execute the Laws of the Union

- To suppress Insurrections

- To repel Invasions

People in the New England states generally opposed the war, and northeastern governors were less than enthusiastic about supplying troops for the cause. The call to deploy militia troops outside their respective states, particularly outside the borders of the U.S., quickly turned into a spirited debate.

The Federalist Party dominated New England at the time, and it was generally more friendly to Great Britain and wary of risking trade relations with a war. They considered the conflict to be a war for unprofitable conquest. Opponents of the war quickly dubbed it “Mr Madison’s War.”

After Congress declared war, the Federalist minority released an address “To Their Constituents, on the Subject of War With Great Britain,” outlining their objections and countering Madison’s arguments for war.

While a minority party, the Federalist and New England opposition hindered the war effort.

Madison appointed General Henry Dearborn senior command of the northeast sector. On June 22, Dearborn sent a letter to the governors of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island with a request for two infantry and artillery companies to defend the coast on Madison’s order.

Recognizing that there would be opposition to the order, Dearborn wrote Madison on June 26, advising that “Our political opponents in, and out, of the Legislature, are endeavouring to inspire as general an opposition to the measures of the Genl. Government as possible,” and outlining the scope of the resistance.

MASSACHUSETTS

Massachusetts Governor Caleb Strong refused to supply troops. His council advised, “they were unable from a view of the Constitution of the United States, and the letters aforesaid, to perceive that any exigency exists which can render it advisable to comply with the said requisition.”

On Aug. 1, 1812, Strong asked the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to weigh in on the issue and determine “whether the Commanders-in-Chief of the militia of the several states have a right to determine whether any of the exigencies aforesaid exist, so as to require them to place the militia, or any part of it, in the service of the United States, at the request of the President, to be commanded by him pursuant to acts of Congress.”

The court, led by Chief Justice Theophilus Parsons, determined the governor was within his rights under the constitution to refuse to release state militia to federal control unless one of the three specific criteria outlined in Article I, Section 8 existed. More importantly, Parsons wrote that it was up to the governor to determine when such conditions existed, not the president.

“No power is given, either to the President or to Congress, to determine that either of the said exigencies do in fact exist. As this power is not delegated to the United States by the Federal Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, it is reserved to the states, respectively; and from the nature of the power, it must be exercised by those with whom the states have respectively entrusted the chief command of the militia.”

The Massachusetts High Court also insisted that this would create “no inconvenience” and that it wouldn’t jeopardize national defense because, “The existence of them can be easily ascertained by, or made known to, the Commanders in Chief of the militia; and when ascertained, the public interest will produce prompt obedience to the acts of Congress.”

Parsons also warned that allowing Congress the power to determine when to call out the militia “would place all the militia in effect at the will of congress, and produce a military consolidation of the states, without any constitutional remedy, against the intentions of the people, when ratifying the federal constitution.“

This is notable, as Parsons was one of the leading federalist proponents of the Constitution in the Massachusetts ratifying convention of 1788. Parson’s views were consistent with the arguments he presented during the ratifying convention – federal power is strictly limited and states have the right and duty to step in to stop overreach.

“But there is another check, founded in the nature of the Union, superior to all the parchment checks that can be invented. If there should be a usurpation, it will not be on the farmer and merchant, employed and attentive only to their several occupations; it will be upon thirteen legislatures, completely organized, possessed of the confidence of the people, and having the means, as well as inclination, successfully to oppose it. Under these circumstances, none but madmen would attempt a usurpation.”

On Aug 5, 1812, Strong sent a letter to Secretary of War William Eustis, along with the opinion of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, outlining his constitutional objections to the request. He concluded by affirming, “I am fully disposed to afford all the aid to the measures of the national government which the constitution requires of me,” but insisting his first duty was to the people of his state.

“I presume it will not be expected, or desired, that I shall fail in the duty which I owe to the people of this state, who have confided their interests to my care.”

In October 1812, Gov. Strong laid out his case in a speech. He pointed out that, “Heretofore it has been understood, that the power of the President and Congress to call the militia into service, was to be exercised only in cases of sudden emergency, and not for the purpose of forming them into a standing army or of carrying on an offensive war.”

He went on to insist that some attributes of sovereignty were retained by the state governments and, “One of the most essential is the entire control of the militia” except in the exigencies mentioned in the Constitution.

In a nod to the 10th Amendment, he wrote:

“This has not been delegated to the United States – it is therefore reserved to the states respectively.”

CONNECTICUT

Connecticut Governor Roger Griswold initially said he would execute the orders, but when the formal request for two infantry companies and two artillery companies to defend coastal areas came through, he also refused, insisting the federal government could not “place any portion of the militia under the command of a continental officer.“

Eustis responded, telling Griswald the order came directly from Madison.

Griswold convened a Council of State that advised not releasing the militia as requested.

Connecticut’s argument rested on the sovereign nature of the states. The committee report emphasized that “the state of Connecticut is a FREE SOVEREIGN and INDEPENDENT state.” On the other hand, the United States are a “confederacy of states” and “not a consolidated republic.”

“The governor of this state is under a high and solemn obligation, ‘to maintain the lawful rights and privileges thereof, as a sovereign, free and independent state’ as he is ‘to support the constitution of the United States,’ and the obligation to support the latter, imposes an additional obligation to support the former.”

The committee also emphasized that the federal government had limited powers over the state militia invoking the principle underlying the 10th Amendment.

“The same constitution, which delegates powers to the general government, inhibits the exercise of powers, not delegated, and reserves those powers to the states respectively. The power to use the militia ‘to execute the laws, suppress insurrection and repel invasions,’ is granted to the general government. All other power over them is reserved to the states.”

Griswold’s council determined that since none of the three constitutional requirements were met, the state was under no obligation to cede control of its militia.

As Nobbs summarized it, “If Connecticut was not being invaded, they contended, the militia would not be called out and would remain absent from Dearborn’s command until the Constitutional requirements were met. The state legislature argued it was an offensive war and not a defensive war and refused to contribute.”

When Dearborn renewed the requisition the following month. Griswold reconvened his Council, and it again advised non-compliance.

“The committee cannot believe, that it was ever intended that [the militia] should be liable, on demand of the president upon the governor of the state, to be ordered into the service of the United States, to assist in carrying on an offensive war. They can only be so employed, under an act of the legislature of the state, authorizing it.”

The committee also noted that should the British retaliate “by an actual invasion of any portion of our territory,” or if there was the threat of such invasion, “the militia will always be prompt and zealous to defend their country.”

RHODE ISLAND

Rhode Island Governor William Jones also convened a council of war after receiving a requisition for troops. On Oct. 6, Jones addressed the Rhode Island General Assembly, reporting that the committee determined, “On the question whether the militia of this State can be withdrawn from the authority thereof, except in particular cases provided for by the constitution of the United States, they are unanimously of opinion, that they could not.”

The council also determined the president did not have the authority to determine whether the constitutional criteria had been met. Instead, “the executive of the State must, and of right ought to be judge.”

Jones concluded by telling the legislature that he was confident the states were taking the proper course.

“It is very much to be regretted that there should exist a difference of opinion between the President of the United States and the government of the individual States in any case, and particularly so as it respects the disposing of the detailed militia, when the nation is involved in war. Satisfied, however, that the principle adopted, and the course this State has pursued on that subject is not only perfectly in agreement with the letter, but with the spirit of the Constitution of the United States, I conceive an adherence thereunto indispensable.”

WE REFUSE!

Resistance to federalization went beyond refusals to call forth the militia by state leadership. Some militia members simply refused to cross the border into Canada as well.

When the commander of the New York militia called out the Chautauqua County regiment, it refused the summons because “no valuable end would be answered by the intended draft.”

Later, efforts to launch an attack into Canada from Ogdensburg failed because 66 of the 400 men refused to cross the border. At the battle of Queenstown in October 1812, more than 1,200 militiamen refused to cross the Niagara River into Canada. And when Dearborn tried to march on Montreal, militia units again refused to invade Canada.

In an 1813 letter to Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Rush summed up the opposition to war in Canada.

“Alas! for the divided state of our citizens, and the distracted state of the Councils of our country!—while I have uniformly considered the War we are engaged in as just, I have lamented the manner in which it has been conducted. The Attack upon Canada appears to involve in it too much of the conquering Spirit of the old world, and is contrary to the professions and interests of Republicans.”

MADISON’S RESPONSE

The situation elicited an angry response from Madison during his annual message to Congress on Nov. 4, 1812.

Madison said the governors’ refusal “was founded on a novel and unfortunate exposition of the provisions of the Constitution relating to the militia” and warned that it could lead to a large standing army.

“It is obvious that if the authority of the United States to call into service and command the militia for the public defense can be thus frustrated, even in a state of declared war and of course under apprehensions of invasion preceding war, they are not one nation for the purpose most of all requiring it, and that the public safety may have no other resource than in those large and permanent military establishments which are forbidden by the principles of our free government, and against the necessity of which the militia were meant to be a constitutional bulwark.”

Ironically, these New England governors were using Madison’s own advice against him. In Federalist #46, Madison had outlined the very strategy used by Griswold and Strong, and supported by Parsons in the Massachusetts ratifying convention – “a refusal to cooperate with officers of the Union” as a way to stop “unwarrantable” federal actions, or even those that were “warrantable,” as Madison described them, yet unpopular. The Salem Gazette reprinted Federalist #46 as a way to embarrass the president and justify the actions of Gov. Strong.

VERMONT

Vermont Governor Martin Chittendon took a similar approach.

On November 10, the governor recalled that portion of Vermont the militia which “has been ordered from our frontiers for the defence of a neighboring State, and has been placed under the command and at the disposal of an officer of the United States, out of the jurisdiction or control of the Executive of this State.”

In an 1813 speech, he said the militia was always considered “peculiarly adapted and exclusively assigned for the service and protection of the respective States” except for when federalized in the three cases outlined in Article I, Section 8.

“It never could have been contemplated by the framers of our excellent constitution, who, it appears, in the most cautious manner, guarded the sovereignty of the States, or by the States, who adopted it, that the whole body of the militia were, by any kind of magic, at once to be transformed into a regular army for the purpose of foreign conquest.”

CONCLUSION

At its core, the debate between the New England Federalists opposed to the use of their militias in “Mr. Madison’s War” was a Tenth Amendment issue. The opposition argued that the states were “free and sovereign” and had delegated only limited powers to the federal government.

As the committee in Connecticut pointed out, the federal government’s authority to use the militia extends only to executing the laws, suppressing insurrection, and repelling invasions. “All other power over them is reserved to the states.”

The battle between New England states and the Madison administration also reveals the power of resistance to thwart federal actions, and it underscores the ability of states to hold the federal government in check.

The New England governors with support from their legislatures used Madison’s own strategy in Federalist #46 against him. By refusing to cooperate with federal orders pertaining to their militias, the New England states created impediments and obstructions to federal actions they viewed as outside constitutional bounds.