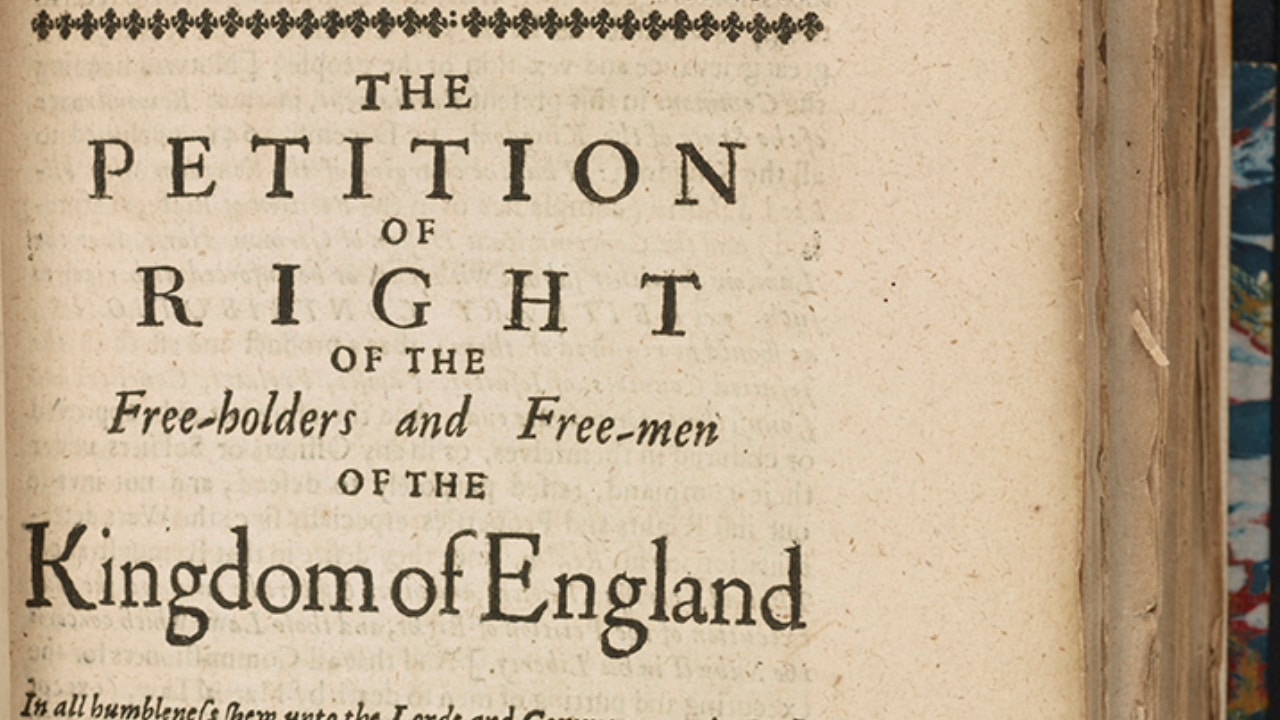

On June 7, 1628 the Petition of Right was ratified by the British Crown in the days preceding the English Civil War. The measure was passed by the Parliament in May and sent to Charles I for his assent, the royal approbation that endowed the writ with force of law.

Of all the concessions granted the King’s subjects in the Petition, one of the most historically well-regarded and readably visible in the image of American liberty is the one mandating that taxes may be levied only by the Parliament. Students of history will recognize the principal provenance of the “no taxation without representation” demand made by the erstwhile Englishmen in America.

Two other crucial provisions of the Petition of Right include the mandate that martial law be declared only in time of rebellion, and the right of a prisoner to know the reason for his incarceration, known as the writ of habeas corpus. A third principle was also distilled into our own constitutional admixture as the Third Amendment — prohibiting the involuntary quartering of troops.

The Petition was passed by Parliament in 1628 under pressure from the people. Englishmen were decrying against Charles I for a roster of royal violations of existing law. A couple of years prior to the uproar that resulted in passage and enactment of the Petition, Charles was in the position of doing a bit of petitioning himself.

In 1626, Charles I needed Parliament to loosen the purse strings in order to fund his protracted war with Spain. The war, under the leadership of George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham was not going well and Parliament was looking to impeach the Duke for his ineptitude. In the ultimate snub to Parliament, Charles not only ignored the impeachment proceedings and the charges rightly leveled against his friend, he appointed Buckingham to the post of Chancellor of Cambridge University and dissolved Parliament in the deal.

Cutting off his nose to spite his face (or save it) left Charles I without recourse to the money necessary to prosecute the Anglo-Spanish War, part of the larger continental conflict known as the Thirty Years’ War. In order to raise the money, King Charles forced extension to the crown of a loan (known appropriately as the “Forced Loan”) from taxpayers without the parliamentary consent. As if this ham-fisted extortion was not enough to force Parliament’s hand in restraining the King, Charles ordered troops to arrest and imprison anyone who refused to pay their share of the loan.

Five of the men incarcerated for their refusal to contribute are known as the “Five Knights. These noblemen petitioned the Court of the King’s Bench in order that they might be informed as to the specific reasons for their apprehension and imprisonment. Charles wisely did not want to be forced into the role as defender of a defenseless exercise of a nonexistent prerogative, so he declared that the knights were being detained not for a specific crime, rather for a purpose known only to “our lord the king.”

In the subsequent hearings on the matter, lawyers for the knights averred that being imprisoned “by special command” of the king was an illegal abrogation of the due process rights of their clients, a right clearly explicated in Chapter 29 of the Great Charter of the Liberties of England (Magna Carta). Therefore, the knights’ counsel argued, if Charles could not enumerate specific charges against them, the knights must be released.

The King did not simply acquiesce and order the knights be set free. In fact, the Attorney General argued on behalf of the crown that the King could rightly imprison a man without charging him with a specific crime if it was a matter of state security. That was, he insisted, the situation in the case at bar, and thus the arrests were not subject to a writ of habeas corpus.

In an attempt to appease the King without appearing to set at naught the Magna Carta and the subsequently enacted laws based thereon, the bench ordered that the knights be held until its decision was issued. The King and his court rightly regarded this equivocation as tacit approbation of its flouting of the rights of the English. It was this haughty disregard for the rights of his subjects that resulted in the issuance and ultimate ratification of the Petition of Right.

The immeasurably influential Sir Edward Coke authored the legislation in Parliament to overturn the King’s Bench’s ruling in the Five Knights Case. Coke’s decision 18 years earlier in Dr. Bonham’s Case as well as his writings were considered so remarkable that Thomas Jefferson once said that “Coke Lyttleton was the universal elementary book of law students.” And John Rutledge stated that Coke’s Institutes should be considered “to be almost the foundation of our law.”

On May 27, 1628 the final draft of the Petition of Right was passed by both houses of Parliament and was sent to Charles I for his signature.

As assented to by Charles I on June 7, 1628, the Petition contained a restatement (and reinforcement) of many of the most fundamental rights enjoyed for centuries by Englishmen. Among them were a few that Americans enjoy as elements of our constitutional protections against government usurpation:

• “no man, of what estate or condition that he be, should be put out of his land or tenements, nor taken, nor imprisoned, nor disinherited nor put to death without being brought to answer by due process of law”;

• “that they [subjects of the King] should not be compelled to contribute to any tax, tallage, aid, or other like charge not set by common consent, in parliament”;

• “no freeman may be taken or imprisoned or be disseized of his freehold or liberties, or his free customs, or be outlawed or exiled, or in any manner destroyed, but by the lawful judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land”;

• “soldiers and mariners have been dispersed into divers counties of the realm, and the inhabitants against their wills have been compelled to receive them into their houses, and there to suffer them to sojourn against the laws and customs of this realm”; and

• “subjects have of late been imprisoned without any cause showed; and when for their deliverance they were brought before your justices by your Majesty’s writs of habeas corpus.”

Despite the obvious import of these hard-won rights on the lives of millions of Americans (and their English ancestors), the anniversary of the Petition of Right was likely ignored by even the most sincere of Constitutionalists. We would do well to remember the words of Roman orator Cicero, “It is good to remember the words of our Founders, but it is better to understand the principles behind those words.”

This article was originally published at The New American and is reposted here with permission from the author.