The “pursuit of happiness” is a foundational principle enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. In the Founders’ view, this was inextricably linked to individual liberty and property rights.

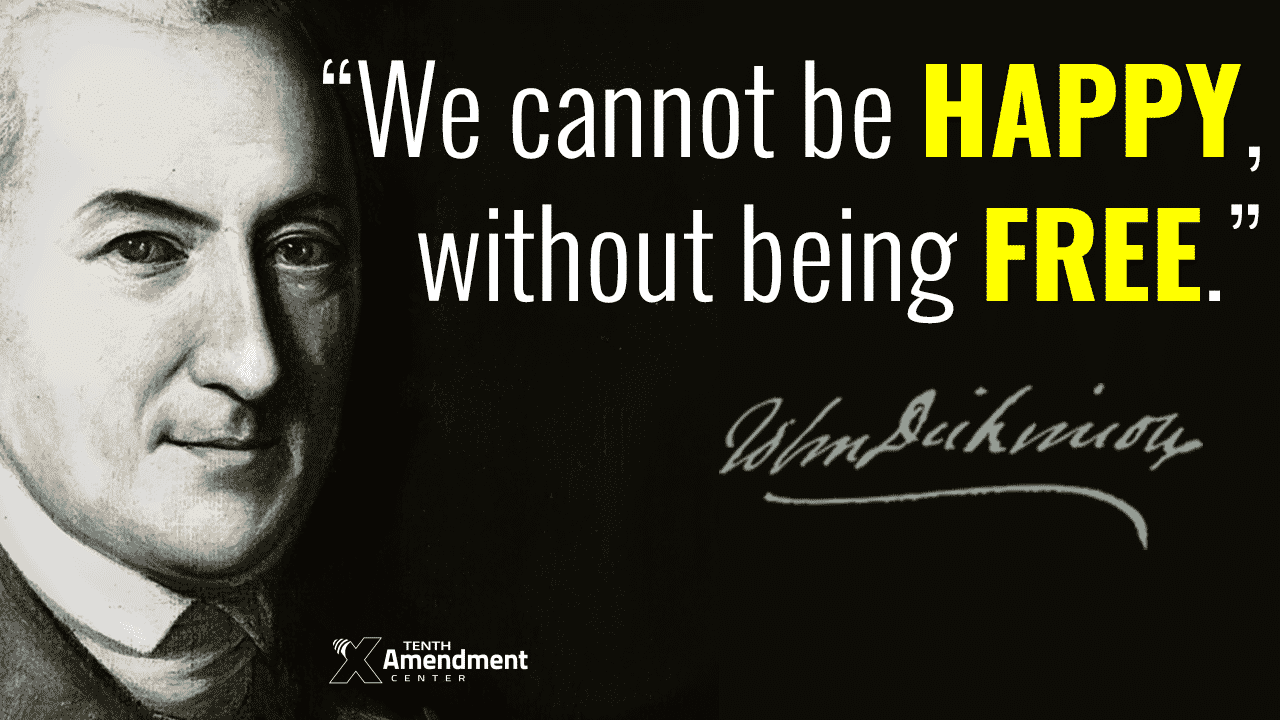

John Dickinson explained it this way in the last of his 12 Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania:

“Let these truths be indelibly impressed on our minds—that we cannot be HAPPY, without being FREE—that we cannot be free, without being secure in our property—that we cannot be secure in our property, if, without our consent, others may, as by right, take it away.”

In short, the “Penman of the Revolution” took the position that the road to happiness is built on freedom, which in turn, is built on property rights.

Dickinson’s Letters were the most widely-read documents on American liberty until the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in 1776. As such, they were a big part of what Thomas Jefferson later referred to as “an expression of the American mind” that helped inform the Declaration of Independence.

We can see these principles clearly expressed in the Declaration when it asserts that everybody has “certain unalienable Rights” and that “among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

HAPPINESS

For many, the meaning of life and liberty is pretty clear, but what did the founding generation mean by “pursuit of happiness?”

The writings of John Locke heavily influenced Thomas Jefferson as he drafted the Declaration. In his Second Treatise on Government, Locke listed “life, liberty and property” as three fundamental natural rights.

While Locke emphasized property as the third fundamental natural right, he also recognized that people naturally seek happiness, and governments should make every effort not to block the path to it.

In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke wrote, “The highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness.”

Locke continued, noting that “The Necessity of pursuing true Happiness [is] the Foundation of Liberty.”

Jefferson, Dickinson, and many other leading founders were heavily influenced by Locke, but other thinkers also informed their worldview.

Swiss philosopher Jean Jacques Burlamaqui was another natural rights philosopher who likely influenced Jefferson to change “property” to the broader idea of “the pursuit of happiness.”

Burlamaqui was extremely influential on the founding generation. Jefferson and James Madison in particular quoted his work liberally. And while he was a die-hard Lockean, we can also see Burlamaqui’s influence on Dickinson’s road to happiness.

In his Principles of Natural Law, Burlamaqui identified the pursuit of happiness as the purpose of all human actions. In a follow-up work The Principles of Natural and Politic Law, organized and published after his death, Burlamaqui expounded on this and tied happiness to property.

“Natural liberty is the right which nature gives to all mankind, of disposing of their persons and property, after the manner they judge most convenient to their happiness.” [Emphasis added]

Locke went on to write, “Nature, I confess, has put into man a desire of happiness and an aversion to misery.” He called these “innate practical principles,” and said they “Do continue constantly to operate and influence all our actions without ceasing: these may be observed in all persons and all ages, steady and universal.”

Jefferson’s decision to include the pursuit of happiness in his trio of natural rights was also likely influenced by George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights. In the first article, Mason asserted that all men have certain inherent rights, including “the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.” [Emphasis added]

Note that Mason also channeled Lockean principles and closely linked the acquisition and possession of property with pursuing and obtaining happiness.

PROPERTY

The term “property” is only mentioned one time in the Constitution. This leads some people to believe that property rights weren’t very important to the founding generation. In fact, as we have already seen, many founders considered property rights the foundation of all others.

Arthur Lee of Virginia wrote An Appeal to the Justice and Interests of the People of Great Britain in 1775. He asserted that “the right of property is the guardian of every other right, and to deprive a people of this, is in fact to deprive them of their liberty.”

This idea finds its roots in the English legal system that set the foundation for American law. It goes all the way back to the Magna Carta (1215), which broadly prohibited the seizure of property without due process.

“No freeman is to be taken or imprisoned or disseised of his free tenement or of his liberties or free customs, or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go against such a man or send against him save by lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land. To no-one will we sell or deny of delay right or justice.”

In his Commentaries on the Laws of England, William Blackstone wrote, “There is nothing which so generally strikes the imagination, and engages the affections of mankind, as the right of property.”

This idea was carried to America by the colonists. James Otis Jr. listed the “right of private property” as one of the three “absolute liberties of Englishmen” along with the right to personal security and the right to personal liberty.

John Adams made a similar assertion years later in 1790 in his Discourses on Davila, calling property as “sacred as the laws of God.”

He went on to write, “Property must be secured or liberty cannot exist.”

During the Philadelphia Convention, John Rutledge of South Carolina reminded the delegates that “property was certainly the principal object of Society.”

Alexander Hamilton made a similar comment, saying, “One great object of government. is personal protection and the security of Property.”

It’s clear that property was not only important to the founding generation, many prominent founders believed the right to property was the foundation of every other.

When we hear the word property today, we generally think of land or physical things. Blackstone defined property as “that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe.”

James Madison affirmed this physical definition of property in his essay on property in 1792, writing, “A man’s land, or merchandize, or money is called his property.”

But he went on to offer a much more expansive definition of property, saying “a man has a property in his opinions and the free communication of them,” and even his religious ideas, along with “the safety and liberty of his person.”

In other words, property is much broader than physical possessions. Our most valuable property is in ourselves – our bodies, our thoughts, our opinions, our labor, and our peaceful actions.

James Madison summed it up this way.

“In a word, as a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights.”

This encapsulates the idea that property is intertwined with our other fundamental natural rights. After all, how can you have liberty in thought and action if you don’t have self-ownership? And without self-ownership, possession of property can never remain secure.

While you won’t see the phrase “property rights” in the Constitution, numerous clauses were included to protect them.

As Robert Natelson pointed out, the Constitution empowered Congress to protect intellectual property by authorizing copyright and patent laws. It outlawed piracy, a property crime. It required direct taxes (mostly importantly property and income taxes) to be apportioned among the states. And it completely prohibited export taxes.

All of these provisions and many more were inserted to protect property. The Bill of Rights went further and prohibited government infringement of “the property of our rights,” including the right to speech, assembly, religion, and to keep and bear arms.

CONSENT

Given the fundamental nature of property rights, many in the founding generation believed it was unjust to take somebody’s property without their consent.

In 1774, John Jay, who later became the first chief justice of the Supreme Court, summed it up succinctly in his Address to the People of Great Britain.

“No power on earth has a right to take our property from us without our consent.”

Samuel Adams made a similar point two years earlier in The Rights of Colonists.

“What liberty can there be where property is taken without consent?”

Like the idea of property rights itself, this notion of consent predated the American Revolution and the drafting of the Constitution.

Even as most people still believed in the “divine right of kings”, thinkers were beginning to grasp the idea that political power ultimately derives from the people.

John Milton expressed this principle in his 1659 The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates.

“It being thus manifest that the power of Kings and Magistrates is nothing else, but what is only derivative, transferr’d and committed to them in trust from the People, to the Common good of them all, in whom the power yet remaines fundamentally, and cannot be tak’n from them, without a violation of thir natural birthright.”

The colonists carried this notion of consent to the New World. In 1657, a Massachusetts court recognized that property could not be taken from another person or even used “without his owne free consent.”

In 1680, Algernon Sidney wrote Discourses Concerning Government. It was published posthumously after the British government charged him with treason and executed him for writing it. Thomas Jefferson considered this book to be the best introduction to the principles of natural law, “which has ever been published in any language.”

Sidney expanded on this idea of consent.

“All those that compose the society, being equally free to enter into it or not, no man could have any prerogative above others, unless it were granted by consent of the whole; and nothing obliging them to enter into this society but the consideration of their own good.”

John Locke reinforced the idea of consent in his Second Treatise on Government published in 1690. He argued that every individual exists in “a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man.”

Given this “perfect freedom,” people can only come under the power of government by their consent.

“Men being, as has been said, by nature all free, equal and independent, no one can be put out of this estate, and subject to the political power of another, without his own consent.” [Emphasis added]

Locke went on to assert that “the only way whereby anyone divests himself of his natural liberty and puts on the bonds of civil society, is by agreeing with other men to join and unite into a community, for their comfortable, safe and peaceable living one amongst another, in a secure enjoyment of their properties, and a greater security against any that are not of it.”

Jefferson carried this idea into the Declaration of Independence,

“That to secure these rights, (life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness) Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Virginia’s ratification of the Constitution put it this way.

“All power is naturally vested in and consequently derived from the people; that Magistrates, therefore, are their trustees and agents and at all times amenable to them.”

It logically follows that if government is supposed to exist only by consent, it likewise cannot take a person’s property – broadly construed as Madison did to include self-ownership of all our rights – without their consent.

And that brings us full circle back to happiness.

It’s self-evident that if the government (or anybody else) can take your physical property or limit the peaceful exercise of your thoughts and actions without your consent, you’ll be unhappy.

John Dickinson nailed it. Happiness depends on freedom, and we can’t be free if our property in ourselves and our things aren’t secure from the arbitrary hands of government.