On his last day in office, James Madison delivered what might be history’s most significant – and overlooked – presidential veto.

This was in response to the Bonus Bill in 1817 – an infrastructure bill, what they referred to as “internal improvements.” In a rare example of both integrity and adherence to the Oath of Office, Pres. Madison vetoed the bill, despite the fact that it directly aligned with his long-professed personal political goals.

He chose the Constitution, despite having an easy out: either signing it or, as Speaker Clay suggested, deferring to his successor, James Monroe.

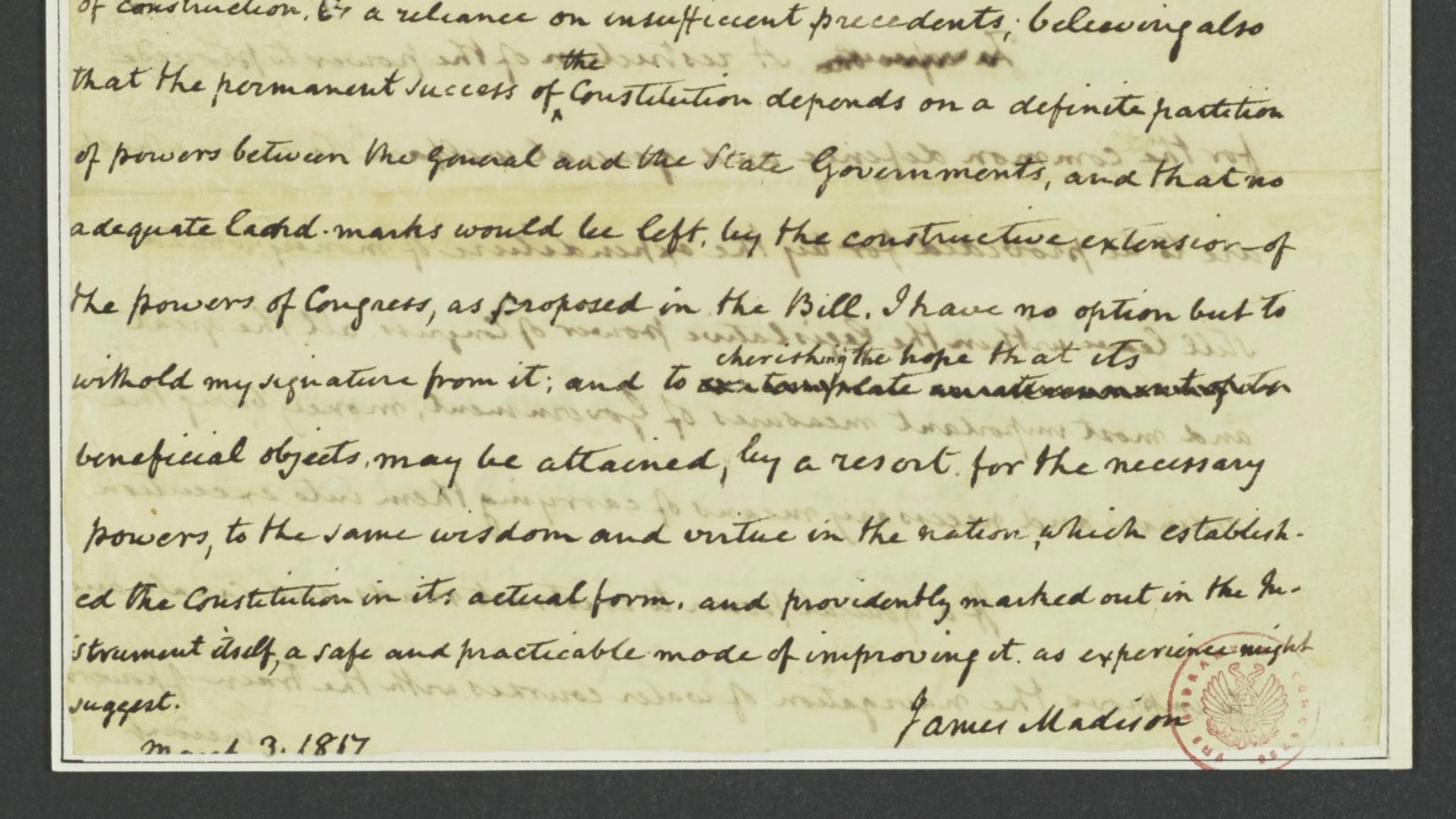

VETO MESSAGE

In his veto message of Mar. 3, 1817, Madison acknowledged his long-standing support of the goal, writing “I am not unaware of the great importance of roads and canals and the improved navigation of water courses, and that a power in the National Legislature to provide for them might be exercised with signal advantage to the general prosperity.”

But for Madison, who had advocated for this kind of federal power for decades – including at the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 – the bill had a fatal flaw. It attempted to exercise power beyond the strict limits of the Constitution.

His veto message made this clear:

“The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in the eighth section of the first article of the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers, or that it falls by any just interpretation within the power to make laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution those or other powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States.”

Bonus Bill supporters, like many politicians today, used a whack-a-mole strategy with the Constitution: first, claiming authorization under the commerce clause, then, if that failed, falling back to the general welfare clause.

But Madison wasn’t convinced of either. Regarding the commerce clause, he wrote:

“The power to regulate commerce among the several States” can not include a power to construct roads and canals, and to improve the navigation of water courses in order to facilitate, promote, and secure such a commerce without a latitude of construction departing from the ordinary import of the terms strengthened by the known inconveniences which doubtless led to the grant of this remedial power to Congress.”

Madison also rejected the general welfare clause argument.

“To refer the power in question to the clause “to provide for the common defense and general welfare” would be contrary to the established and consistent rules of interpretation, as rendering the special and careful enumeration of powers which follow the clause nugatory and improper.”

He continued, with a warning that trying to shoehorn the legislation into the clause would establish a dangerous precedent and turn the system from, as he put it in Federalist 45, one of “few and defined” powers into one of nearly unlimited power.

“Such a view of the Constitution would have the effect of giving to Congress a general power of legislation instead of the defined and limited one hitherto understood to belong to them, the terms “common defense and general welfare” embracing every object and act within the purview of a legislative trust.”

EXPANDING POWER

Madison had long advocated for power over “internal improvements,” including proposals at the 1787 Philadelphia Convention. He discussed this in a letter to Reynolds Chapman:

“Perhaps I ought not to omit the remark that altho’ I concur in the defect of powers in Congress on the subject of internal improvements, my abstract opinion has been that in the case of Canals particularly, the power would have been properly vested in Congress. It was more than once proposed in the Convention of 1787; & rejected from an apprehension, chiefly that it might prove an obstacle to the adoption of the Constitution.”

In his Seventh Annual Message to Congress, he again urged action.

“Among the means of advancing the public interest the occasion is a proper one for recalling the attention of Congress to the great importance of establishing throughout our country the roads and canals which can best be executed under the national authority.”

But Madison also included a caveat – use the amendment process to enlarge the powers of congress to get it done.

“It is a happy reflection that any defect of constitutional authority which may be encountered can be supplied in a mode which the Constitution itself has providently pointed out.”

Madison repeated his call – and caveat – in his eighth and final Annual Message to Congress.

“I particularly invite again their attention to the expediency of exercising their existing powers, and, where necessary, of resorting to the prescribed mode of enlarging them, in order to effectuate a comprehensive system of roads and canals”

The veto closed with a reminder: adhere to the Constitution’s limits and use the amendment process – the only safe way to authorize additional power:

“I have no option but to withhold my signature from it, and to cherishing the hope that its beneficial objects may be attained by a resort for the necessary powers to the same wisdom and virtue in the nation which established the Constitution in its actual form and providently marked out in the instrument itself a safe and practicable mode of improving it as experience might suggest.”

A last-minute effort to override Madison’s veto failed.

INTEGRITY

In his final act as President of the United States, the Father of the Constitution stuck with the Constitution.

One need not even agree with James Madison’s view that the “national authority” was the right spot to place this kind of power to recognize that choosing to follow one’s oath over one’s personal political goals, especially when the latter would have been quite easy to do – is the type of integrity we should all be demanding of anyone and everyone in office today.

It’s a high bar, but in order to build a real “land of the free” instead of the largest government in history, maybe “we the people” need to raise our standards.