Remember, remember the Fifth of November.

On November 5, 1765, a long-running holiday celebration in New England turned into a protest against British taxation and overreach.

Pope Night evolved out of Guy Fawkes Day, an English holiday commemorating the thwarting of the infamous Gunpowder Plot.

In 1605, Fawkes was part of a group that concocted a scheme to kill Protestant King James I and replace him with a Catholic monarch. Tipped off by an anonymous letter, authorities discovered Fawkes in the undercroft beneath the House of Lords guarding gunpowder intended to blow up the upper house of Parliament.

Colonists brought the celebration of Guy Fawkes Day with them to America. Pope Night, as the New England colonists called it, was initially a rather somber observance to reinforce Protestant values and uplift the British monarchy, but it morphed into a night of revelry, particularly for the lower classes in New England.

By the 1740s, gang violence was an institutionalized part of Pope Night, particularly in Boston.

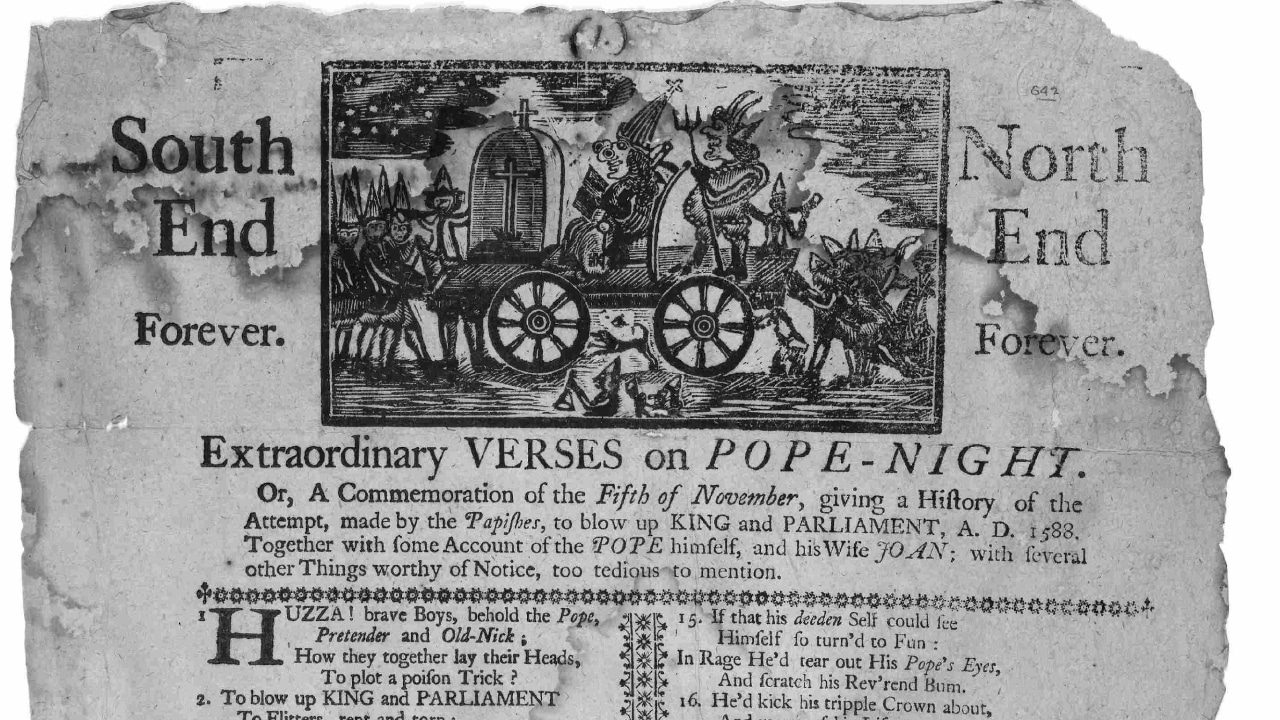

The South End and North End gangs primarily made up of working class men and boys staged parades featuring elaborate effigies of the Pope, the Devil, and sometimes Catholic prince James Stewart. As the parades moved toward each other in the center of town, marchers would demand donations from wealthy Bostonians to offset the cost of the festivities. There was an implicit threat of violence if the donations were not forthcoming.

Once the two gangs came together, they would fight and try to seize the other side’s effigy. If the North End won, they would burn the effigies on Copp’s Hill. If the South Side won, the effigies met their demise at Boston Common.

The celebration was inherently violent. Isaiah Thomas participated in a Pope Night celebration and later wrote about it.

“Hostilities soon commenced … In those battles stones, brickbats, besides clubs were freely used and altho’ persons were seldom killed, yet broken heads were not infrequent.”

By 1765, Pope Night had taken on a revolutionary note. On Nov. 5, 1765, the two sides in this Bostonian battle instead united against a common foe — the British government.

The passage of the Stamp Act in March 1765 raised the ire of the colonists. It was the first internal tax levied directly on American colonies. The act required all official documents in the colonies to be printed on special stamped paper. This included all commercial and legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, and even playing cards.

As historian Dave Benner explained in his article on the Stamp Act, the standard American position held that the act violated the bounds of the British constitutional system. Objecting to the notion that Parliament was supreme and could impose whatever binding legislation it wished upon the colonies, the American colonists instead adopted the rigid stance that colonists could only be taxed by their local assemblies. They claimed this principle stretched all the way back to 1215 and the Magna Carta.

The Stamp Act went into effect on November 1, just days before Pope Night. Unsurprisingly given the widespread anger in the colonies, the annual night revelry in Boston turned into a protest against the hated law.

Bostonians had already launched several protests against the Stamp Act. On the night of Nov. 5, Ebenezer Mackintosh and Samuel Swift, leaders of the South and North End gangs respectively, brought the rivals together. They marched as one through Boston with what was later called a ‘union pope.’

John Hancock and other patriot merchants provided them with food, drink, and supplies.

As OldNorth.com described it, “This act foreshadowed the years of Bostonian resistance of what they viewed as Parliament’s encroachment on their rights and liberties.”

Mackintosh was a prominent figure at the Pope Night festivities. He was known to mock the upper class by marching “attired in a blue and gold uniform and a lace hat bearing a rattan cane and a speaking trumpet.” He quickly became a street leader as resistance to the Stamp Act grew. Mackintosh and the South End Gang participated in violent protests against the act prior to Pope Night, most notably participating in a mob that burned down the home of Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Colonial action against the Stamp Act and the colonists’ refusal to cooperate with it effectively nullified the law and forced the British to repeal it.

Pope Night came to an end as the American Revolution turned into a shooting war and the colonies worked to build an alliance with Catholics in Canada. In 1775, George Washington wrote a letter calling for an end to Pope Night revelry.

“As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form’d for the observance of that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope—He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are solliciting, and have really obtain’d, the friendship and alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause…”