The Boston Tea Party is arguably the best-known event leading up to the war for independence, but a number of leading Revolutionaries, including Benjamin Rush and John Adams, held that it actually started in Philadelphia.

Resolutions adopted during a Philadelphia town meeting on Oct. 16, 1773, set the stage for the Boston Tea Party in December and another lesser-known tea party in the City of Brotherly Love just weeks later.

TAX ON TEA

On May 10, 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act. The law actually lowered the price of tea from the East India Tea Company because it undercut prices charged for smuggled tea. Lord North, who initiated the legislation, thought the colonists would be happy to pay less for Company tea.

But there was a caveat.

After significant resistance, the widely-hated and opposed Townshend Acts of 1767-68 were mostly repealed by 1770. However, an import duty on tea was retained in order to reaffirm that Parliament continued to hold authority to tax the colonies, per the Declaratory Act of 1766, which claimed power over the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

The colonists were well aware of the situation, and despite the lower prices, they vehemently opposed the Tea Act because of this assertion of parliamentary power.

Benjamin Franklin summed up colonial grievances in a letter to Thomas Cushing.

“It was thought at the Beginning of the Session, that the American Duty on Tea would be taken off. But now the Scheme is, to take off as much Duty here as will make Tea cheaper in America than Foreigners can supply us; and continue the Duty there to keep up the Exercise of the Right. They have no Idea that any People can act from any Principle but that of Interest; and they believe that 3d. in a Pound of Tea, of which one does not drink perhaps 10 lb in a Year, is sufficient to overcome all the Patriotism of an American!” [Emphasis added]

In a letter to Franklin later that year, Cushing agreed.

“I cannot well Conceive of any one measure that would tend more Effectually to unite the Colonies than the present Act impowering the East india Company to Export their Tea to America.”

Franklin emphasized the fundamental dispute between Britain and her colonies. By granting an exclusive tax break to the East India Company, but still maintaining part of the Townshend duties, Parliament was able to “keep up the exercise” of its claimed authority under the Declaratory Act.

RESPONSE

News of the Tea Act reached the colonies in October 1773, along with reports that shipments of tea were en route.

On October 11, Thomas Mifflin, writing under the pen name Scaevola, published a widely distributed pamphlet titled “By Uniting We Stand – By Dividing We Fall.” Scaevola was a prominent Roman jurist and one of the originators of civil law. For a number of years, he was “Tribune of the Plebs,” the first office of the Roman state that was open to commoners, and considered the most important check on the power of the Roman Senate and magistrates.

Mifflin addressed the letter to East India Company agents in Philadelphia, “You are marked out as political Bombardiers to demolish the fair structure of American liberty.”

He also warned that “the eyes of ALL” were fixed on them, and in comparing the Tea Act to the hated Stamp Act, argued that it didn’t differ “in one single point.”

“If there be any difference . . . the Stamp Act was sensibly felt by all ranks of people; but the Tea Act [is] more insidious in its operation . . . Under the first, no man could transfer his property; . . . even read a newspaper without seeing and feeling the detestable imposition . . . under the Tea Law, the duty is afterwards laid on the article, and becomes so blended with the price of it, that, although every man who purchases tea imported from Britain must pay the duty; yet, every man does not know it, and may therefore not object to it.”

The pamphlet was later printed by newspapers, including the Boston Gazette, and Country Journal on Oct. 25, 1773.

Five days later, a town meeting convened in the Philadelphia State House (known today as Independence Hall). Led by well-known patriot leaders including Dr. Benjamin Rush, Colonel William Bradford, Thomas Mifflin, Dr. Thomas Cadwalader, and other local leaders and members of the Philadelphia Sons of Liberty, the meeting adopted eight resolutions protesting the Tea Act.

The resolutions first asserted support for natural rights and property rights: “that the disposal of their own property is the inherent right of freemen; that there can be no property in that which another can, of right, take from us without our consent; that the claim of Parliament to tax America is, in other words, a claim of right to levy contributions on us at pleasure.”

From there, the resolutions went on to take the position that such taxation without consent, “has a direct tendency to render assemblies useless and to introduce arbitrary government and slavery.”

The resolutions called the Tea Act “an open attempt to enforce this ministerial plan and a violent attack upon the liberties of America,” asserted, “it is the duty of every American to oppose this attempt,” and that opposition to it “is absolutely necessary to preserve even the shadow of liberty.”

The resolutions effectively called for action to stop East India Tea from being unloaded in the colonies.

“Whoever shall, directly or indirectly, countenance this attempt or in any wise aid or abet in unloading, receiving, or vending the tea sent or to be sent out by the East India Company while it remains subject to the payment of a duty here, is an enemy to his country.”

The principles and strategy employed by the Philadelphia committee were essentially the same as those taken by Patrick Henry in his resolutions against the Stamp Act.

The resolutions also called for those appointed by the company to receive and sell tea “from a regard to their own characters and the peace and good order of the city and province, immediately to resign their appointment.”

Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette promply published the resolutions, marking the first public protest against the Tea Act in any of the Colonies.

RIPPLE EFFECT

News of the resolutions soon spread to other colonies.

On October 21, the Committee of Correspondence of Massachusetts sent a letter to other committees of correspondence urging other colonies to take action against the Tea Act.

“We cannot close without mentioning a fresh Instance of the temper & Design of the British Ministry; and that is in allowing the East India Company, with a View of pacifying them, to ship their Teas to America. It is easy to see how aptly this Scheme will serve both to destroy the Trade of the Colonies & increase the revenue. How necessary then is it that Each Colony should take effectual methods to prevent this measure from having its designd Effects.”

On November 5, a town meeting in Boston at Faneuil Hall adopted the Philadelphia resolutions as their own. It declared, “The sense of this town cannot be better expressed than in the words of certain judicious resolves, lately entered into by our worthy brethren, the citizens of Philadelphia.”

Boston wasn’t the only city to affirm the Philadelphia resolutions.

On December 7, the Citizens of Plymouth, Massachusetts, adopted resolutions declaring it their duty to “not only oppose this step as dangerous to the liberty and commerce of this country, but also to aid and support our brethren in their opposition to this, and every other violation of our rights.”

“The dangerous nature and tendency of importing teas here by any person or persons, especially by the India Company, as proposed, subject to a tax upon us without our consent are extremely well expressed by the late judicious resolves of the worthy citizens of Philadelphia.”

ACTION

In a letter dated December 10, Thomas Cushing informed Benjamin Franklin that there was growing sentiment to resist the Tea Act. He pointed out that the law “has greatly alarmed the People here who have had several Meetings upon the Occasion,” and that “they insist upon the Consignee’s sending back the Tea and have determined it shall never be landed or pay any duty here.”

Six days later, members of the Sons of Liberty boarded three British ships in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water.

Just weeks later, a protest in Philadelphia was less violent but arguably more effective.

On Christmas day 1773, the British tea ship Polly commanded by Captain Ayres sailed up the Delaware River toward Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The ship carried a cargo of 697 chests of tea consigned to the Philadelphia Quaker firm of James & Drinker.

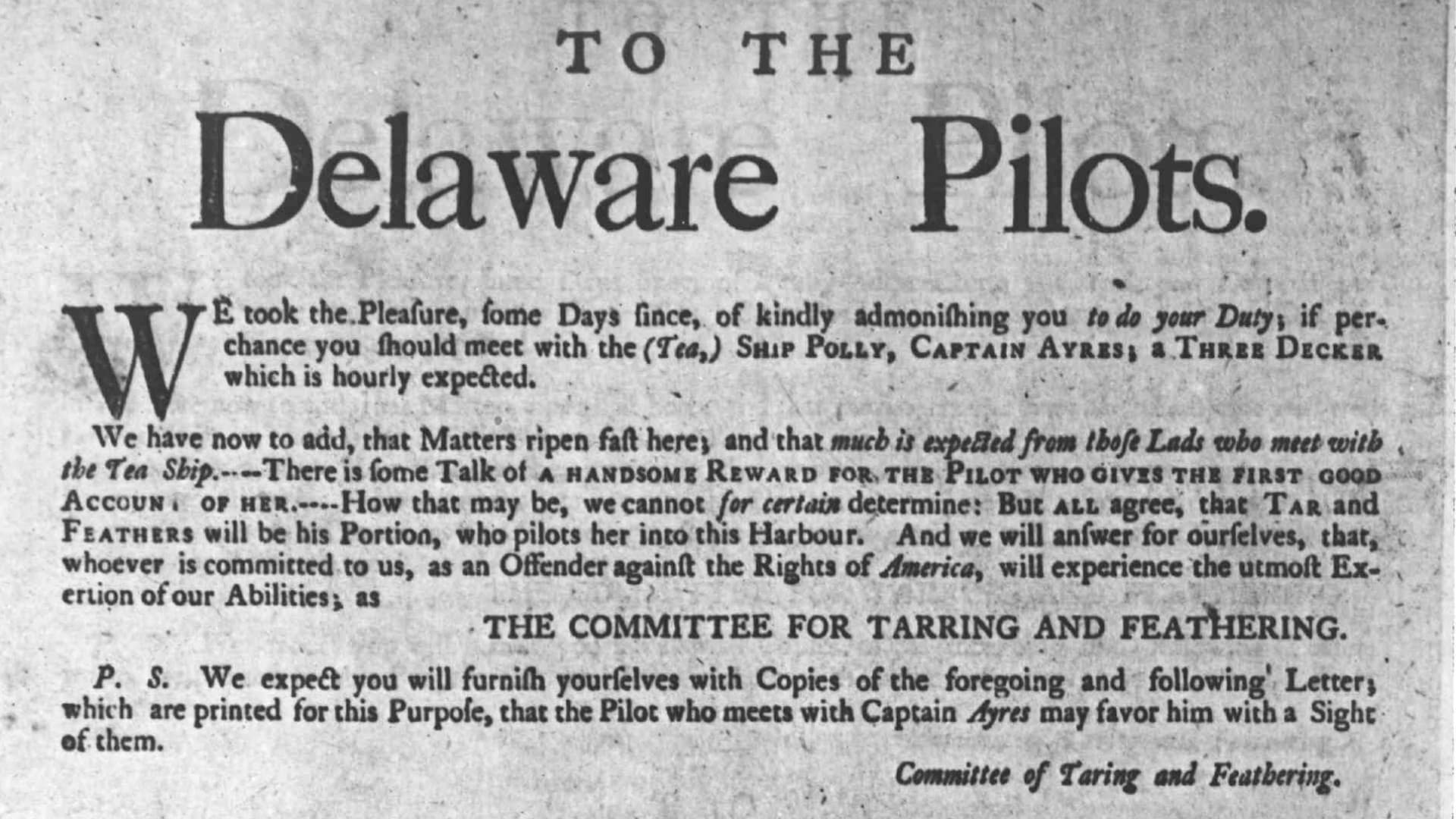

On November 27, a letter sent to the Delaware Pilots, who guided oceangoing vessels in and out of the harbor, warned they would receive harsh treatment if they tried to bring in the Polly:

“WE took the Pleasure, some Days since, of kindly admonishing you to do your Duty; if perchance you should meet with the ( Tea, ) Ship Polly, Captain Ayres; a Three Decker which is hourly expected. … ALL agree, that Tar and Feathers will be his Portion, who pilots her into this Harbour. And we will answer for ourselves, that, whoever is committed to us, as an Offender against the Rights of America, will experience the utmost Exertion of our Abilities; as THE COMMITTEE FOR TARRING AND FEATHERING.”

When the ship got close, it was intercepted nearby in Chester, Pennsylvania, and Captain Ayers was escorted to Philadelphia by several city leaders. On Dec. 27, over 6,000 people met at Independence Hall to discuss how to proceed. At the time, it was the largest gathering held in the colonies.

The meeting decided to order the ship to return to England without unloading its cargo and passed resolutions stating “the tea… shall not be landed” and “Capt. Ayres shall carry back the tea immediately.”

Ayres agreed, probably influenced by a broadside published by the “Committee on Tarring and Feathering.”

“What think you Captain, of a Halter around your Neck—ten Gallons of liquid Tar decanted on your Pate—with the Feathers of a dozen wild Geese laid over that to enliven your Appearance?

Only think seriously of this—and fly to the Place from whence you came—fly without Hesitation—without the Formality of a Protest—and above all, Captain Ayres let us advise you to fly without the wild Geese Feathers.”

The resolutions of December 27 also expressed full support for the actions resisting the landing of tea in Boston and elsewhere.

“This assembly highly approve of the conduct and spirit of the people of New York, Charles-Town, and Boston, and return their hearty thanks to the people of Boston for their resolution in destroying the Tea rather than suffering it to be landed.”

AFTERMATH

The British responded to the Boston Tea Party by passing the “Coercive Acts” to punish the colonies – particularly Massachusetts. These included the Boston Port Act closing the Boston Port, the Massachusetts Government Act stripping virtually all authority from the colonial government, the Administration of Justice Act stripping authority from local courts and authorizing trials to be held in Great Britain instead of Massachusetts, and the Quartering Act allowing British troops to take over private buildings.

Rather than causing division and isolating Massachusetts, Britain’s heavy hand further united the colonies. Committees of correspondence began coordinating organized resistance throughout the colonies leading to the First Continental Congress and ultimately the Declaration of Independence.

Years later in an 1809 conversation, Benjamin Rush and John Adams credited the Philadelphia resolutions for sparking the movement toward independence, saying “the active business of the American Revolution began in Philadelphia.”

“The flame kindred on that day soon extended to Boston & gradually spread throughout the whole Continent. It was the first throe of that Convulsion which delivered great Britain of the United states.”

As the British clamped down on the colonies in the wake of the tea parties, Benjamin Franklin seemed to understand the gravity of the moment. In a public letter published by a London newspaper, Benjamin Franklin protested the measures, asserting that Parliament “appear to be no better acquainted with their History or Constitution than they are with the Inhabitants of the Moon.”

Franklin went on to warn, “You may reduce their Cities to Ashes; but the Flame of Liberty in North America shall not be extinguished. Cruelty and Oppression and Revenge shall only serve as Oil to increase the Fire. A great Country of hardy Peasants is not to be subdued. In the Grave which we dig for the Inhabitants of Boston, Confidence and Friendship shall expire, Commerce and Peace shall rest together.”