Can former President Donald Trump be disqualified from another presidential term? The answer to that question partly hinges on the answer to this one: Does the “disqualification” language in the Constitution’s 14th amendment apply to a candidate seeking the presidency?

In the Colorado case on the subject, the trial judge answered “No, it doesn’t.” She concluded that the 14th amendment’s disqualification language applies to many offices, but not to the presidency. Therefore, she dismissed the case against President Trump.

But the state supreme court answered “Yes,” and reversed the trial judge.

This issue probably will not go away. The judiciary of other states and the U.S. Supreme Court may have to consider it.

The 14th Amendment and the Colorado Supreme Court

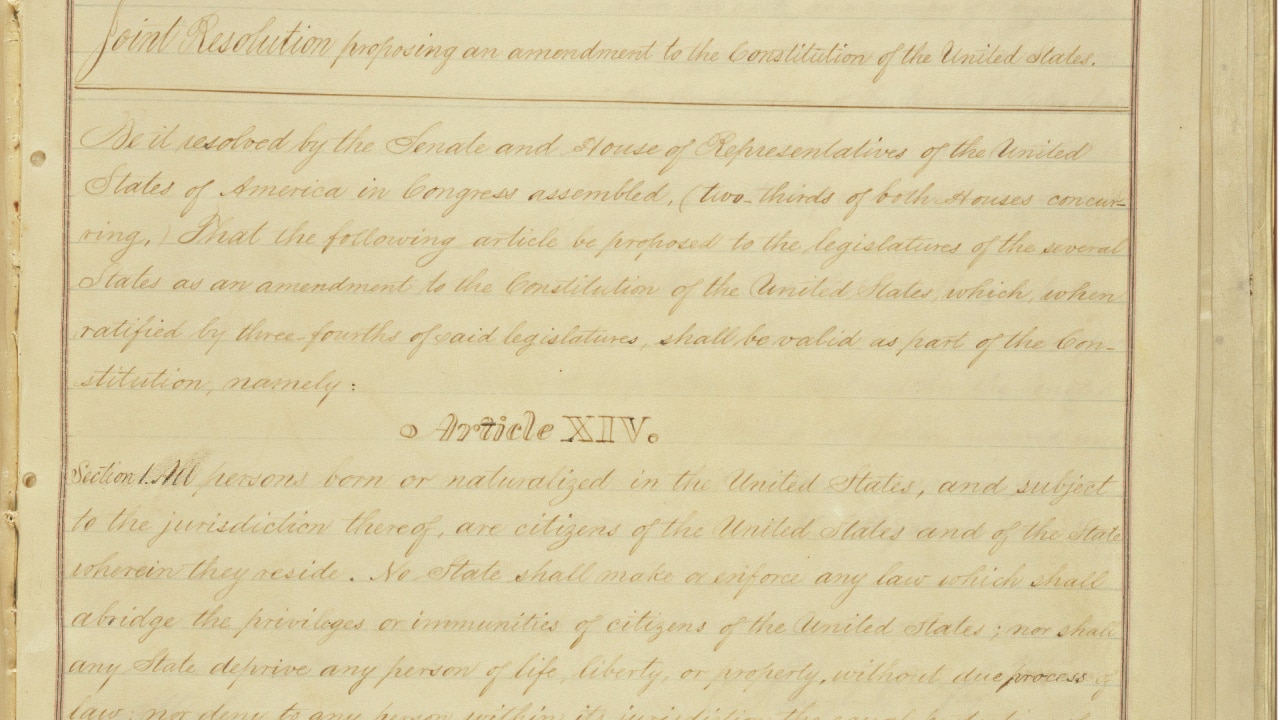

Section 3 of the 14th amendment disqualifies anyone who has “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the [United States]” from certain listed offices. The listed offices include Congress, presidential electors, and “any office . . . under the United States . . . .”

The presidency and vice presidency are not listed—at least not explicitly. However, the justices of the Colorado Supreme Court, like many other writers, claimed the presidency is included because it is an “office . . . under the United States.”

The Colorado justices wrote, “When interpreting the Constitution, we prefer a phrase’s normal and ordinary usage over secret or technical meanings that would not have been known to ordinary citizens in the founding generation.”

But that comment sells the Constitution’s framers short. They were highly skilled legal drafters who knew what they were doing. The document they produced was straightforward. It had no “secret” meanings—even if modern writers ignorant of 18th century conditions might think it did.

The court’s comment also sells short the people who ratified the Constitution. The founding generation was an unusually literate one in legal matters. The phrase “Office under the United States” was the obvious successor to the extremely common British term “office under the Crown.” As former subjects of the British Empire, members of the founding generation had heard and used that expression all their lives.

We must never assume the Constitution’s ratifiers did not understand a legal phrase in a legal document as important, as closely examined, and as widely discussed as the Constitution.

What Does the Original Constitution Mean by “Office Under the United States?”

The Colorado justices disregarded substantial evidence that when the Constitution uses the phrase “Office under the United States,” it refers only to appointed offices such as the Secretary of State or the Secretary of the Treasury. This evidence suggests “Office under the United States” does not include elected offices, such as Senators, Representatives, the Vice President, or the President.

Here is the background:

The Constitution uses certain key terms over and over again. Among them are the words “Office” and “Officer.” Sometimes the Constitution does not modify those words. But on other occasions, the Constitution adds phrases, such as “of United States” or “under the United States.”

Over a decade ago, Seth Barrett Tillman, an American legal scholar working in Ireland, noticed that the use of these “office” phrases is not haphazard. He found patterns. These patterns appear both in the drafting process and in the finished Constitution. Prof. Tillman also identified other historical facts consistent with the patterns.

Since that time, Prof. Tillman has been joined by another legal scholar, Josh Blackmun. Together, they have tried to reconstruct the meanings of all these words and phrases.

They concluded that, as the Constitution suggests, the bare term “Office” includes the presidency. But they also concluded that when the Constitution modifies that word with “of the United States” or “under the United States,” it means only appointed officers. (They also found a distinction between “officer of” and “officer under,” but that distinction is not important here.)

Professors Tillman and Blackmun therefore determined that neither “Office of the United States” or “Office under the United States” includes elected positions. Excluded are members of Congress, the President, and Vice President.

Professors Tillman and Blackmun back this up with a fair amount of proof. For example:

- In British practice the term “officers under the Crown” referred only to appointed, not elected, positions.

- The Constitution states that the President “shall Commission all the Officers of the United States” (Article II. Section 3). In other words, the President gives each officer of the United States papers that confirm and explain the officer’s authority. But commissioning yourself would be, shall we say— awkward. And no one has ever seriously suggested that the President must commission himself or other elected officials. So the President must not be an “Officer of the United States.”

- The Constitution (Article II, Section 4) authorizes impeachment of “The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States.” If the President and Vice President were officers of the United States, there would be no need to list them separately.

- The Constitution treats the oaths of the President and members of Congress separately from the oaths of “Officers of the United States.”

- Then there is the Constitution’s Foreign Emoluments Clause (Article I, Section 9, Clause 8). It prohibits officers under the United States from accepting gifts from foreign officials. Yet President George Washington accepted such gifts without any public objection. True, most people were leery of criticizing Washington, but President Thomas Jefferson was otherwise criticized savagely, but not for the gifts he received from foreign officials. All this suggests that the members of the founding generation did not think of the President as an “Officer under the United States.”

- During President Washington’s first term, the Senate asked Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to make a list of all officers “under the United States.” Hamilton’s list included all appointed positions. It excluded all elected ones, including the presidency.

I am not saying the Tillman-Blackmun evidence is conclusive. Some of the events they rely on occurred after the Constitution was ratified. As I have explained elsewhere, such evidence generally should receive little weight in reconstructing how the ratifiers understood the Constitution several years earlier. On the other hand, the Tillman-Blackmun evidence from the 1790s does have the virtue of being uncontradicted.

What Does the 14th Amendment Mean by “Office under the United States?”

I began to immerse myself in the record of the American Founding over 30 years ago. Much later, I turned my attention to the adoption of the 14th amendment. Congress proposed that amendment in 1866, and its ratification was completed in 1868.

What I discovered is that those responsible for the 14th amendment—drafters, proposers, and ratifiers—mostly were well-meaning. But they were nowhere near as competent as the framers and ratifiers of the original Constitution.

Those responsible for the 14th amendment simply did not have the Founders’ wide knowledge, drafting ability, or understanding of what they were trying to say. This, I believe, is a principal reason disputes over so many key 14th amendment phrases continue to afflict us today.

There is a rule of legal interpretation that tells us what to do when faced with this kind of uncertainty. The rule is that when an amendment uses a word or phrase from the original Constitution, we should presume that the amenders used the phrase the same way the original Constitution does. This suggests that “office under the United States” in the 14th amendment means the same thing as in the original Constitution. To my knowledge, there is no strong evidence to the contrary.

So if the president is not an “officer under the United States” in the original Constitution, then he’s not one in the 14th amendment either.

Why Exclude the President?

Why would those responsible for the 14th amendment disqualify a former insurrectionary from most other offices, but not from the presidency? This is another area in which the amendment’s drafters and ratifiers were exasperatingly unclear. But here are some possible reasons:

First: All of the disqualified officers listed in the 14th amendment are chosen within individual states. Without a disqualification rule, the chances were good that one-time Confederate states, such as Virginia and Mississippi, might choose former Confederate insurrectionaries to serve in state positions or in Congress.

On the other hand, the President is elected nationwide. When the 14th amendment was adopted, the eleven former Confederate states comprised less than a third of all states. And they held less than a quarter of the national population. The chances of a former Confederate being elected President were effectively “zero.”

Second: Although the presidency is a national office, the mechanics of presidential elections are fixed by state officials within each state. If a presidential candidate could be challenged as a former insurrectionary, state officials would have to determine whether this was true. The conclusion might differ from state to state—resulting in the very situation that threatens us now.

The threatened uncertainty may have induced those responsible for the 14th amendment to avoid that risk by excluding presidential candidates from formal disqualification. After all, the chances of a former Confederate being elected President were nil anyway.

Third: The 14th amendment permits Congress, by a two-thirds vote of each house, to remove a disqualification. Those responsible for the 14th amendment may have concluded that if a former rebel was, by some miracle, elected President, his election represented forgiveness by an authority even higher than Congress: the people of the United States.

Fourth: If the presidency were among the offices from which a candidate could be disqualified, a former insurrectionary seeking the job might bargain with Congress to remove the disqualification. This could lead to all sorts of corruption. It might also result in the presidency’s submission to Congress.

These are all serious considerations. They should not be dismissed lightly.